CNC machining centers and turning centers are used for countless applications, which is why almost every manufacturer has these machines in their shops. Paralleling company diversity is the wide spectrum within each utilization factor:

Lot size – At one end of the spectrum are companies that regularly run under 10 workpieces per lot. At the other end are companies that dedicate CNC machines to running one part, day in and day out.

Repeat business – Some companies repeatedly run a finite number of different workpieces, while others never see the same job twice.

Lead times – Some companies have days, weeks or even months to get ready to run jobs, while others must provide same-day services.

These are among the most important utilization factors. Others that vary among CNC users include profitability, tolerances held, materials machined, available personnel/skill levels, average setup time, average program execution time, and complexity of work. With a little thought, you can probably come up with several more.

Knowing these diversities exist, CNC manufacturers do their best to provide features aimed at satisfying all of their customers. Indeed, some features are important to and appreciated by everyone. Features like decimal point programming, radius designation for circular motion, and hole-machining canned cycles can be regularly applied without negative side effects.

Other CNC features are not so benign. The CNC manufacturer may be targeting a niche application, like small lots or often repeated jobs, or helping with unique setup-related issues. Misapplication of these features will result in wasted time, wasted or duplicated effort and/or wasted material (scrap). Here, I expose four such CNC features as well as how and when they could be misapplied. More importantly, I ask you to consider other misapplications that may exist in your own shop.

Are Conversational Controls Always the Best Programming Option?

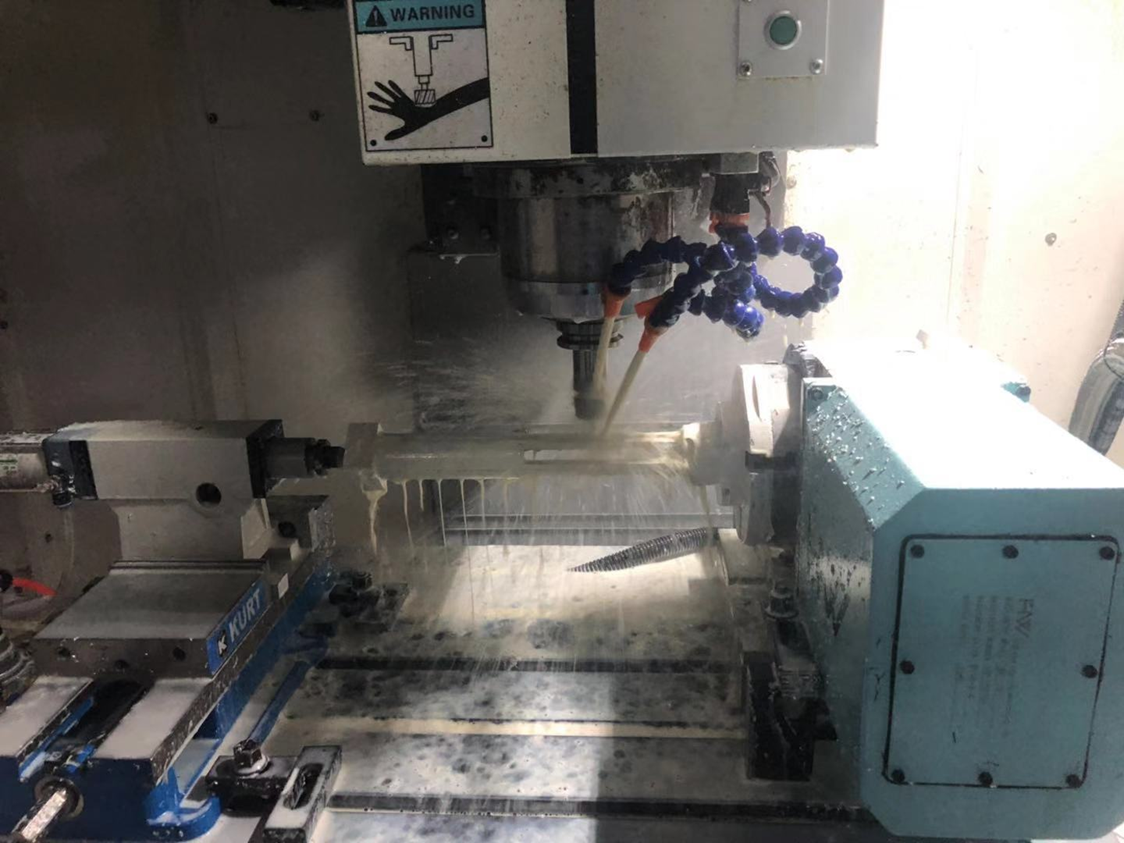

Conversational controls enable shopfloor programming. They are best applied when the machine commonly runs small lots of seldom-repeated jobs—relatively simple workpieces with short to medium program execution times—and especially when one person is responsible for everything related to the job, including programming. Many contract shops have machines matching these criteria.

However, as lot sizes grow and jobs are repeated—with more complex workpieces requiring longer run times and/or when more people are available to help with the CNC process—the benefit of shopfloor programming fades.

At Samshion, our engineers and operators have seen this transition firsthand. In early prototyping stages, conversational controls allowed them to quickly create programs for small experimental runs. But as customer demand grew and the same parts were produced in higher volumes, the time spent manually entering code began cutting into spindle uptime.

Samshion’s programming team eventually moved to an offline CAM system integrated with the shop’s network. Now, while one machine runs, engineers prepare and optimize programs for the next project. Operators simply call up the pre-tested code, minimizing downtime. This shift increased overall equipment efficiency by over 25% in repeat production.

So, while conversational controls remain a powerful tool for quick setups and prototypes, their misuse in repetitive production is a silent productivity killer.

How Can Tool Length Compensation Be Used More Efficiently?

There are two ways to use machining center tool length compensation. While programming remains the same for each, operation techniques are dramatically different. The best method for your shop is largely determined by how CNC personnel are utilized.

With one method, the tool length compensation value is the distance in the Z-axis from the tool tip to the Z-axis program zero surface. It is measured during the setup, meaning the machine must be used as a kind of (very expensive) height gauge. This is only appropriate if tool length compensation values must be measured by the operator while the machine is down between production runs, which is often the case in contract shops.

With the other method, the tool length compensation value is simply the tool’s length. Assuming the company has the resources (personnel and tooling components), cutting tools can be assembled and measured—possibly in the tool crib—while the machine is in production. Tool length compensation values can even be automatically entered by a measuring device.

At Samshion, this practice is standard. Tools are preset in an external measurement station connected to the digital tool library. Once a tool is loaded, the CNC automatically retrieves its length data from the network. Samshion’s setup technicians no longer touch off tools manually, reducing human error and slashing setup time by 70%.

By turning tool measurement into a parallel process—done outside the machine instead of during downtime—the company saves hours of idle time each week. This reflects one of the most important Lean principles in manufacturing: separating value-added work (machining) from non-value-added work (manual setup).

Should Every Setup Require New Fixture Offsets?

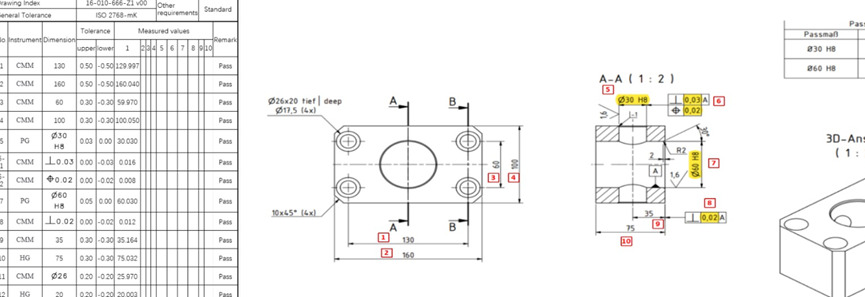

There are two ways to use fixture offsets, based on whether setups are qualified—aligned with the machine table in such a way that the workholding device can be precisely placed and replaced.

If there is very little repeat business for a machine, it can be difficult to justify the extra cost of qualifying a workholding setup. In that case, the setup person must measure the distance in each axis from the machine’s reference position to the program zero surface. These values are manually entered into the related fixture offset registers and must be remeasured every time the setup is made.

The second method, used when setups are qualified, allows program zero assignments to remain the same every time the setup is reinstalled. A programmed command can even enter these values automatically. With FANUC CNCs, it’s possible to shift the reference point for fixture offset entries to a more logical location—especially helpful with subplates or modular fixturing.

At Samshion’s production floor, qualified setups are the rule rather than the exception. Using zero-point clamping systems, operators can swap fixtures in under five minutes, confident that the offsets are already accurate. This consistency not only accelerates setup but also ensures dimensional reliability.

For example, during a stainless-steel enclosure production run, the Samshion setup team reused a fixture designed for a previous batch. Thanks to the qualified system, they started cutting within minutes—no need to re-probe, no time wasted.

By eliminating repetitive offset measurement, the team freed up machine capacity for more production work—a crucial advantage in high-mix manufacturing environments.

When Should Tool Nose Radius Compensation Be Avoided?

With FANUC turning centers, tool nose radius compensation (G41/G42) lets programmers specify the relationship between the cutting tool and the workpiece. The setup person must then enter tool type and nose radius values in the offsets.

This works perfectly when CNC programs are written manually. But when a CAM system is used, the toolpath already accounts for the nose radius. Entering those offsets again at the control duplicates the compensation, potentially causing geometric errors.

At Samshion, engineers discovered this issue during a complex shaft machining project. Operators unknowingly entered nose radius offsets on the control, despite the CAM path already compensating for it. The result was a 0.2 mm deviation on all diameters—small but unacceptable for the tolerance range.

After reviewing the workflow, the Samshion programming department standardized a rule: all CAM-generated programs disable control-based nose radius compensation. The CAM environment now stores complete tool geometry data, ensuring precision while reducing the operator’s cognitive load.

This change simplified setups and improved communication between engineers and machinists—illustrating how digital consistency prevents costly misapplications.

Summary: When and Where Does Waste Occur?

Serious waste occurs when:

1.A company with repeat business, predictable lead times, long program execution times, and complex work still uses conversational controls.

2.A company with adequate resources requires setup personnel to measure tool lengths on the machine instead of off-machine.

3.A company with qualified setups still requires re-measurement of program zero every run.

4.A company using CAM still requires manual tool nose radius compensation input.

Each of these practices introduces unnecessary downtime, human error, or material waste—hidden inefficiencies that collectively erode profit margins.

Expanded Professional Analysis & Insights

The article effectively highlights the importance of applying CNC features according to the production environment—an often-overlooked foundation of manufacturing optimization. Below is a professional analysis expanding on the original ideas with real-world context, modern examples, and Samshion’s engineering perspective.

1. How Does Utilization Diversity Shape CNC Decisions?

Modern CNC shops differ widely in strategy. A small-batch prototype facility values flexibility and speed, while a high-volume production shop prioritizes repeatability and automation. Samshion’s engineers regularly evaluate utilization factors—lot size, material variety, and lead time—to decide which CNC functions truly add value.

For instance, Samshion’s prototype division runs 50 different jobs weekly, each requiring unique setups. Conversely, the mass-production unit might run a single part for weeks, fine-tuning cycle time. Aligning CNC features with these realities prevents wasted effort.

2. Conversational Controls in Modern Shops

Conversational systems like Mazatrol or Haas CNC Control remain ideal for rapid, low-volume work. Yet in Samshion’s integrated environment, these systems are complemented—not replaced—by offline CAM programming.

An operator can still tweak dimensions directly on the control for one-off jobs, but for production runs, pre-validated CAM programs maintain speed and consistency. This hybrid workflow blends flexibility with scalability—ensuring the right tool for each task.

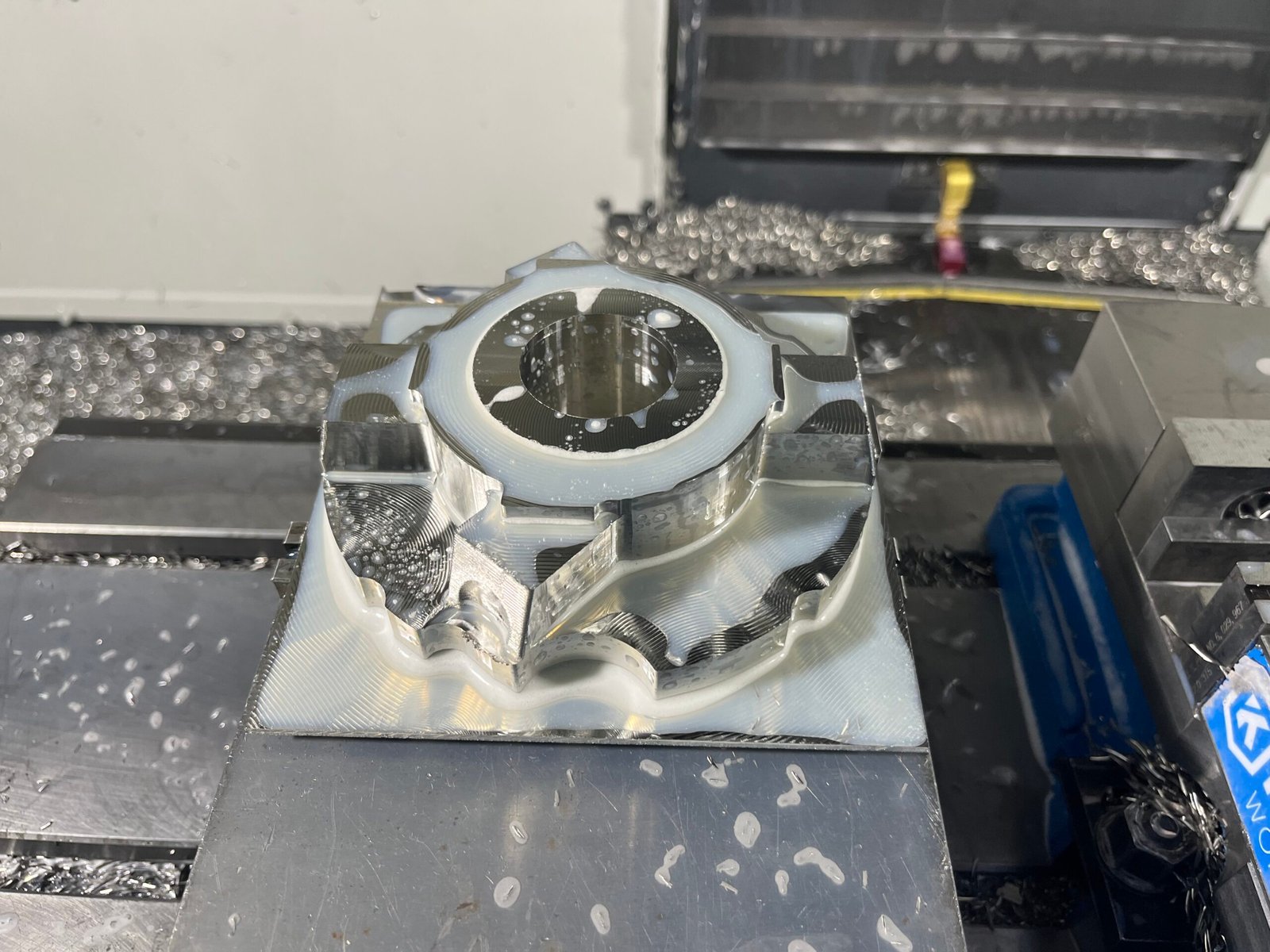

3. Tool Presetting and Automation Integration

In Samshion’s tool room, every cutting tool is measured on a digital presetter. The tool’s ID, length, and diameter are uploaded automatically to the machine database. Once inserted, the operator confirms the tool ID, and the offsets load automatically—no manual typing, no downtime.

This automated loop—between engineer, operator, and system—embodies Industry 4.0 thinking: human expertise combined with digital precision.

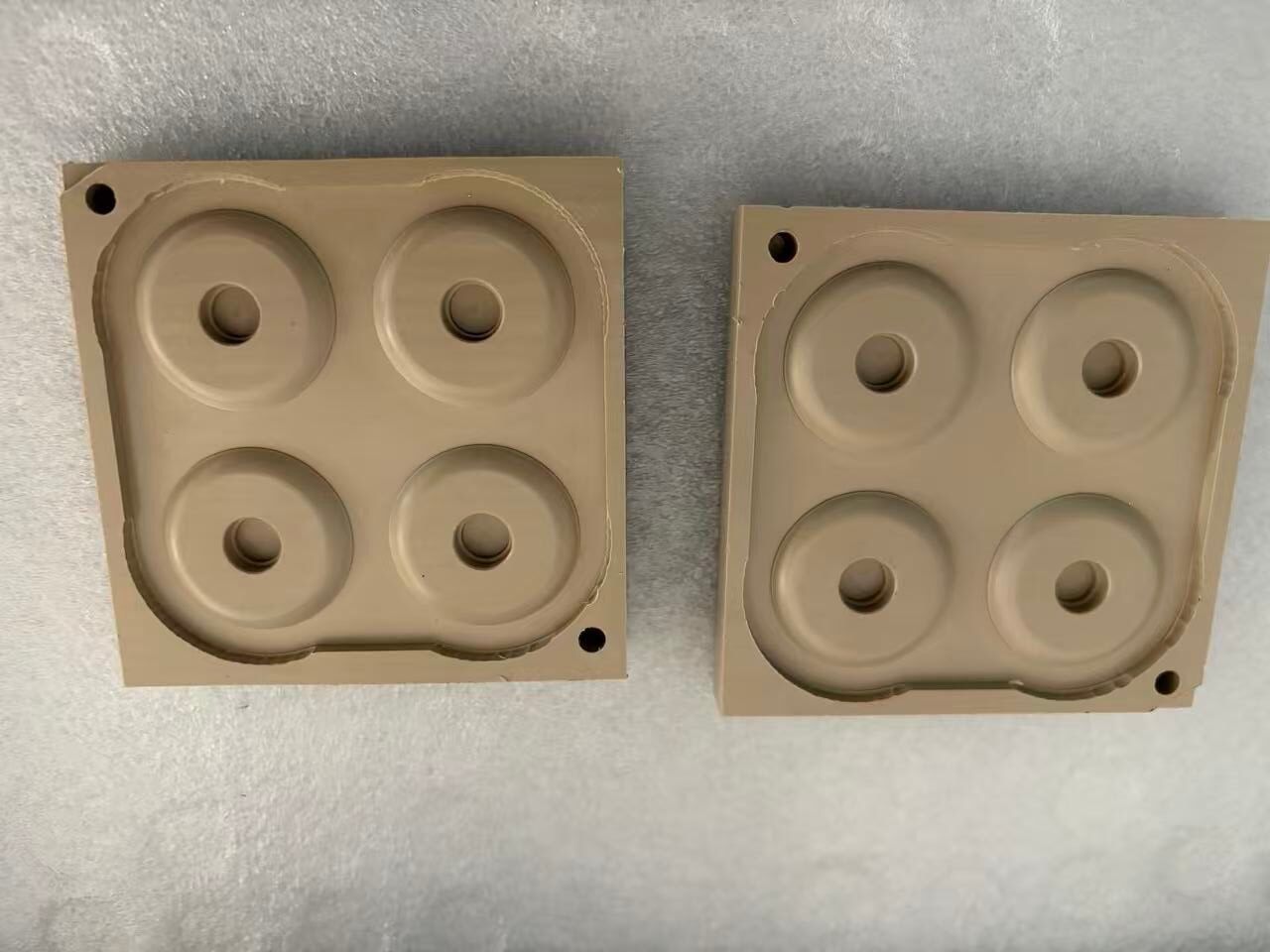

4. Fixture Standardization and Zero-Point Systems

Fixture repeatability is a cornerstone of lean machining. Samshion engineers have implemented subplates and quick-change fixtures across departments. What once took 90 minutes now takes 15 minutes—with sub-0.01 mm repeatability.

By combining mechanical precision with software consistency (standard offset files and QR-coded fixture IDs), the team drastically reduced rework and operator guesswork.

5. Digital Tool Path Accuracy

When engineers rely on CAM for geometric compensation, the software’s virtual model becomes the “source of truth.” Operators no longer need to remember which offsets to apply. This prevents duplication errors, allowing Samshion’s machinists to focus on monitoring cut conditions instead of managing numbers.

6. Wastes and Lean Manufacturing Principles

Every misapplied CNC feature equates to one or more of the seven wastes identified in Lean manufacturing:

Waiting: Machine idle while operators program or measure.

Overprocessing: Duplicate compensation entries.

Motion: Unnecessary setup adjustments.

Defects: Scrap from incorrect offsets.

By reviewing each process through this lens, Samshion’s process engineers identify and eliminate inefficiencies proactively.

7. Human Roles and Communication

CNC efficiency relies as much on people as on technology. In Samshion’s workflow, programmers, setup technicians, and operators share digital setup sheets generated automatically from CAM data. Each document includes tool IDs, offsets, and verification steps—ensuring everyone operates from the same information source.

This communication framework prevents “tribal knowledge” errors—when one operator’s undocumented adjustment causes inconsistencies later.

8. Automation and Smart Manufacturing

In an era of robotics and data-driven production, manual compensation steps no longer fit. Probing systems now auto-correct offsets; smart coolant systems adjust flow dynamically; and IoT dashboards track spindle uptime in real time.

Samshion’s automation initiative connects machines, measuring stations, and databases through a central control hub. By eliminating manual input at every stage, the team achieves greater repeatability, reduced cycle time, and predictive maintenance capabilities.

9. Implementing These Lessons

To apply these insights effectively, Samshion management follows a structured improvement model:

1.Map Current Practices – Identify where manual setups or redundant programming exist.

2.Standardize – Define best practices for tool and fixture handling.

3.Digitize – Connect CAM, presetters, and machines via software.

4.Train – Equip engineers and operators to recognize when a CNC feature helps—or hurts—efficiency.

This framework ensures continuous improvement, aligning human skill with technological capability.

Conclusion: Turning CNC Knowledge into Productivity

Every CNC feature—from conversational programming to tool compensation—was designed with a specific scenario in mind. When used appropriately, these features enhance productivity and precision. When misapplied, they quietly drain efficiency.

By fostering collaboration between Samshion’s engineers, programmers, and operators, and by leveraging automation intelligently, CNC operations can evolve from manual craftsmanship to digital excellence.

Efficiency, after all, isn’t just about cutting faster—it’s about thinking smarter, aligning process with purpose, and making every second of machine time count.